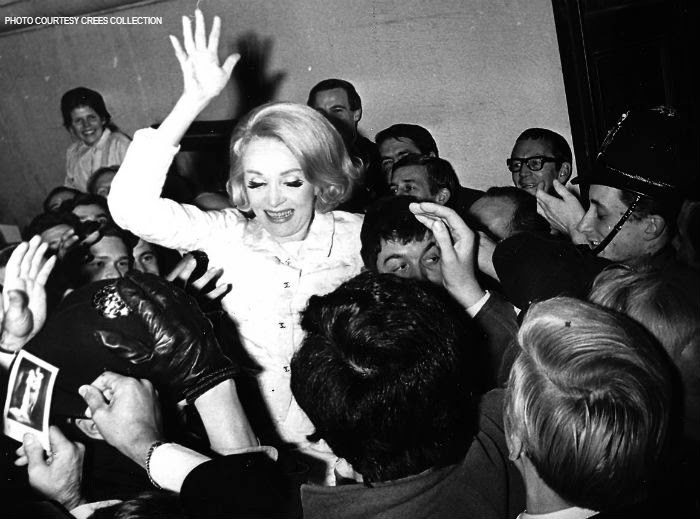

Betty Best interviewed Marlene Dietrich, backstage at London's Golder's Green Hippodrome, in 1965. Special thanks to the Crees Collection for sharing this material.

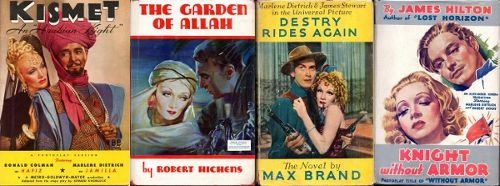

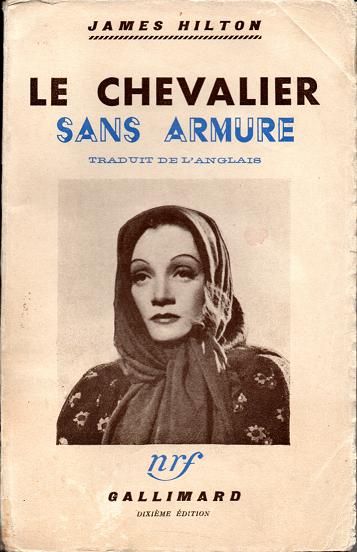

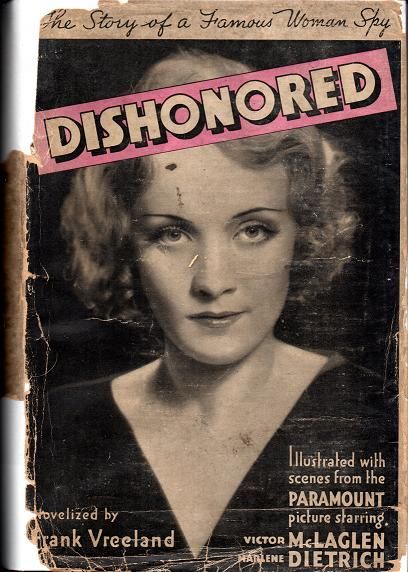

![]() |

| Marlene Dietrich in her dressing room. |

It had been a month since I'd seen her. A month since she'd held out a delicate, tiny hand and agreed to the idea of a private interview with a brief, "Yes, yes, call me at Claridges"– and sounded as if she meant it.

But I'd made at least ten telephone calls every day since then, from Brighton to Birmingham and back to London, without ever once getting through to that inimitable, halting voice. A month of pleading with agents and publicity officers, all of whom sounded terrified at the very thought that I should claim a whole hour of Miss Dietrich's time to myself.

By then my mental picture of her was becoming a little unsure. Perhaps that brief meeting among a horde of people in the excitement of a first arrival had been misleading. Perhaps the apparent ease and friendliness of the magic Marlene was just an effect, switched on like her magnificent stage personality, for an audience which expected it.

Police cordons

![]()

In between times I'd heard of the packed schedule of a tour which stopped in each city for only a week, which included intense rehearsals with each orchestra, with her arranger

Burt Bacharach (who flew from the U.S.A. especially), an entire one-woman radio play for the BBC somehow jammed into the London week; of fantastic hold-ups every night after each show while fans besieged the stage doors so that Dietrich could not emerge without special police cordons.

Perhaps I was hoping for too much. Then I got word that she was fed up with English reporters asking about nothing but her age, her looks, her clothes, and that most forbidden of all subjects, her family – about whom she will never speak.

All the signs were against my ever getting to see her at all. Yet, throughout I had a curious belief that it would come off – because of the geranium.

Miss Dietrich had, that first night, told an endearing story: ''I've just made a new LP. The songs of old Berlin as I remember them as a child. They are beautiful songs, real songs of the people. And because they always meant so much to me, I wanted to do everything about this record myself. Even to designing the cover. Me, I'm not an artist. But I had my ideas. I always see Berlin as a grey city – grey walls, streets, everything.

"So I got paints and made a beautiful grey pattern. Then, because I'm not an artist, I went to a stationer's and bought those letters children use to scratch with a pencil and that come out on paper.

"Then on the bar of the 'H' at the end of my name I put a lovely little pot of bright red geraniums. When I took it proudly to the publisher, he said, 'Why the geraniums there?' I tried to explain that it is the flag of the little people in grey cities everywhere. The big gesture of the bourgeois toward beauty. And I am a bourgeois and I love geraniums.

"But, of course, he couldn't understand. Never mind, I kept my geranium on the cover – just as I always keep one in my dressing-room wherever I go."

And sure enough, when finally, after many cancellations, I got to her dressing room at Golder's Green Hippodrome on the outskirts of London, there it was. Not a grand florist's specimen,but a simple little scarlet single in a common terracotta pot sitting on the wash basin in the corner.

Beside it on the wall was a symbol of that very private side of Dietrich's life she seldom mentions, a

large framed and inscribed portrait of Ernest Hemingway, wearing a polo-necked sweater and looking young and adventurous.

On a previous occasion I had once managed to get her to touch on her great friend ship with this man who wrote of her: "I think she knows more about love than anyone. I know that every time I have seen Marlene Dietrich she has done some thing to my heart and made me happy.''

It was when she was railing against the agonies of work on tour: "It is not the performances I mind. They are fine. Once I am in front of people I can recharge my batteries from them.

''It is the terrible chore of packing and unpacking. Of never having a minute to myself or a second for reading."

Then someone asked who was her favourite author and, suddenly, the whole face softened and glowed. She replied with the single word, "Hemingway."

She began to speak of the great respect and love she felt for him; her voice broke, she turned away with a final, "Life is not the same now he has gone."

Bag of heather

Beside his picture, which so dominated the little room at the Hippodrome, hung a pair of pink satin ballet point shoes and a bag of heather. The first looked like a tribute from Russia, the second reminded me of her fondness for Scotland and her unashamed superstition.

Nearly half the heather blossoms had fallen from their sprigs, so I guessed she had carried it with her at east all last year since she first appeared at the Edinburgh Festival.

It was there she said she had the greatest surprise of her life as far as a doting audience was concerned. In the cool dark after midnight the entire audience had lined up outside the stage door, not only to cheer but to walk her all the way home to her hotel.

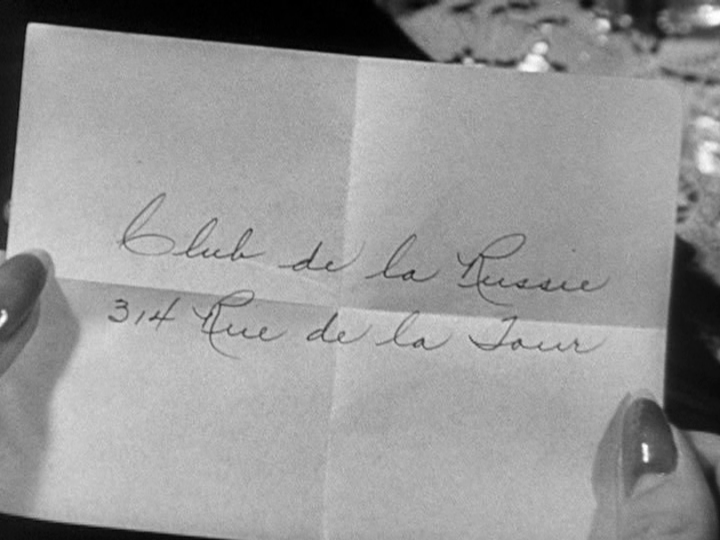

Directions

I had just time to glance around the dressing-room and to notice the gossamer fine, flesh-tinted chiffon gown embroidered with diamonds lying under a fresh white tissue on the chaise-longue when there was a flurry at the door and in came Marlene.

Behind her was Tony Chardet, H. M. Tennents' stage manager for the English tour. His face was a picture of intense concentration. Miss Dietrich marched straight to her bag on the dressing table, extracted a handful of scaled envelopes with a christian name on each, in bold, determined handwriting, and handed them to him with quick, precise directions.

"Here are the lists. This one for Eileen, this for Tom. Oh, now I have one somewhere for Blezard. Yes, here it is. Now everything is there tell them, everything. Someone should clean that room with all the flowers. It is a mess, yes?"

She had him back out through the door. I took a deep breath ready to begin, but Miss Dietrich had thought of something and was speaking to someone else through the door. For three more minutes her meticulous organising continued.

Then she was with me – but only just.

"Oh, there is so much to do.

"People ask me why I don't have six people travelling with me to do it. I say by the time I've explained how I want it I could have finished doing it myself, and as I want it.

"It was different last year when my daughter was with me. She knows how it is done without discussion. Now I must do it myself."

![]()

Over on the wall-shelf sat a small pincushion in yellow velvet and a businesslike needle case. Miss Dietrich picked them up, went to the

chaise-longue and began to turn a sleeve of the famous Jean Louis gown inside out with infinite care.

"Can I help you?" I ventured.

"No, no, it is better for me to do it. The diamonds are set in metal. They catch the material. It is so delicate it tears."

She reversed the sleeve over a specially folded white napkin, settled herself on the couch, cut a small piece of spare chiffon and began to patch the sleeve.

Somehow there seemed nothing odd in the fact that this 20th-century goddess of glamour was settling down to a little home sewing job. She was completely at home with it and looked more than competent.

The voice went on with out a glance in my direction: "Last night they threw hundreds of flowers onto the stage. I stooped down to pick some up and put my elbow through the sleeve. Look. That dress was not made for bending..."

The first smile I'd seen that day lit her lovely, sad face. "No, it is not," she added.

"Jean Louis is the best designer in the world. He is in Hollywood, you know. He has always made my stage costumes for me. It is not only the design, but also the workmanship.

"I shall go to Los Angeles for five days on my way to Australia for him to work on my gowns. I cannot get such craftsmanship anywhere else, not even in Paris.

"You see the metal settings? When we designed this dress we tried to make it with unset stones. It was flat under the lights – nothing. Set in metal there is a true jewelled effect."

Like a glittering second, skin

I remembered the time a year ago I had first seen that dress. The house lights went down, the orchestra blared forth with Falling In Love Again, and into the spotlight at the side of the blackened stage stepped the glittering, golden figure.

From the diamond choker at the neck to the tips of her shoes and the end of her finely boned wrists, the gown clung like a second skin alive with flashing fire. The entire audience gasped. It was sheer magic, and the dress now being patched with loving care was part of that magic.

For a moment I wished the bravo-ing audiences could see her now.

Without looking up from her work she answered my questions about her first night in London on this trip.

"Oh, it was fabulous. So many hundreds had waited outside the stage door I just could not get to my car. They would not let me through. I tried for a quarter of an hour and even with two policemen helping it was hopeless.

"One of the policemen, a nice young man, said he would ring for reinforcements. He went to the public phone inside. After he had talked for a while I went in and asked him, 'Who are you calling?''Scotland Yard,' he said.

"I could not believe him. It sounded too much like a film.

"I said: 'But you don't call Scotland Yard for me. That's for big things,' and took the phone myself and asked, "Who is it?'

"Back came the answer, 'Scotland Yard.' Then they said 'We hear you're in trouble, we're sending all we can get!'

"I laughed and thought they were mad until a little later a big shiny black van came up with 30 men in it!

"Even then they had to form a cordon around the car when I was in it because people at the back always push the ones in front and I won't let my driver begin until they are safely away. It would be so easy to hurt someone.

"Oh, but the whole thing was unbelievable. Now the men come regularly every night or I can't get home."

The pure joy of this escapade was reflected in her eyes. They sparkled with pleasure like a child's. It was clearly one more tale she would treasure and tell again and again like the Edinburgh walking home, or the Polish audiences who came from their villages to kneel at her hotel door.

"They brought me their cherished medals to show they knew I had been with them during the war. So many from concentration camps who knew I worked against the Nazis, who told me it had helped them to know that someone they respected was working for them outside.

"We still don't know how their underground movement got the messages through to them. But they knew and never forgot."

When she tells this her eyes fill with tears.

Her compassion for people in trouble is obvious the greatest impetus in all the more serious songs she sings.

"Where Have All The Flowers Gone? is a passionate plea for peace; Shir Hatan, a ballad in Hebrew from Israel of the lonely, hungry child, a call for sanity and help for children everywhere.

Even "Lili Marlene," of which she says ''it is not the song they cheer at the end. Their applause is for me as a person and what I did during the war. They all remember.

No doubt this is why her clothes, even the Chanel suits with their simple boxy jackets and pleated skirts, carry a little embroidered strip of scarlet over the left breast.

It is the Legion d'Honneur which she was awarded after her constant travels through the war zones of Europe when millions of Allied servicemen heard that husky, insinuating voice, and took heart.

I asked, "Do you believe that someone like yourself going between nations of Europe, here, and in Australia can help international understanding?"

It helps to cry, and to laugh

"Maybe not on the great scale we need now. But, yes, a little.

"When I went to Israel in 1960 there had been a ban on the German language ever since the war. Even in opera it could not be sung. I understood after all they had been through. But I said, 'I must try it or I lose a lot of songs from my program I'm not counting on losing. If they start hating it I stop.'

"But when I sang German songs they wanted more and more. They let me sing in German because they knew my past history."

"Do you believe, then, that the job you do will help prevent war?"

Her face became even sadder, almost despairing.

"There'll always be war. There always has been, no? I can't say I really believe this helps. The people who hear and respond to my songs already agree with my philosophy of humanity.

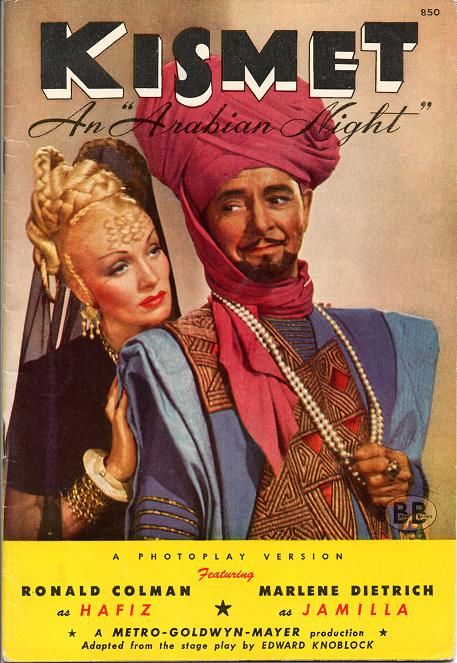

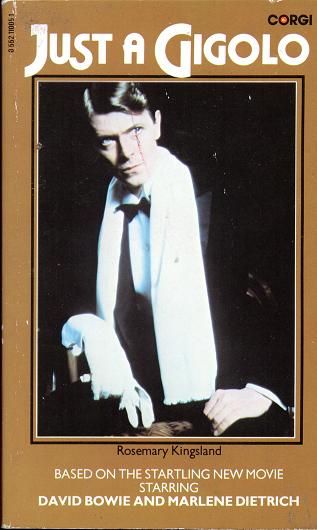

![]() |

| Marlene in Warsaw, at the Ghetto Heroes Monument. |

"There is not a human being alive who wants war. I have never met one. But it's not the people who govern the world. Power always lies with people who have interests other than humanity. You can never get a message like this through to people who want money and power. They cannot hear."

"Then what do you want to give with your performance?"

"Emotion. Emotion. People want to be emotion ally disturbed. To feel free to cry – and to laugh.

"I only want to go to the theatre to cry. The artistic things I remember, in books, in a theatre, are always the sad ones."

"Why?"

"I suppose it goes right back to the fairy tales we heard when we were children. And all the greatness of Shakespeare, all that upheaval."

"Your performances to me are like an intimate dialogue with each member of the audience," I said.

Suddenly she was happy again. "Yes. You have noticed that? Each performance is different, that is

why. It is most intimate in countries where people have suffered; in Holland, for instance, where you may think people are not very emotional.

"Every time I sing in Amsterdam they cry, and I cry. Tears flow all the time. It is wonderful. Also in

Russia and Poland – and, of course, Israel."

"You once said you were brought up to think very little about yourself. Isn't that hard for an actress?"

"On the contrary. This profession is like a continuation of that upbringing. Ours is the one profession where you can't go to the boss and say 'I have a headache or a fever' and he lets

you go home.

"If an actress does not turn up to work they say she is drunk or something awful. That phrase 'The show must go on' may sound corny. But it is strictly true. We go on no matter how bad we feel.

"The theatre is a wonderful teacher. Whatever the profession demands you must obey. It is impossible to bring your private worries into the theatre and indulge them. You do the show and that's that.

"This is very Anglo-Saxon, isn't it? Look at the British people. They proved they could take so much. I admire this. They never take themselves too seriously.

"Well, that is how I was brought up."

"Is that how "Is that how you brought up your own daughter, Maria?" Just for a second she looked cross. I had gone out of bounds to mention a member of her family. Then she decided perhaps I was speaking more generally. She gave me one warning look not to pry further and then:

"I tried. But it is not easy in America. You cannot make a child a lone wolf. It is not fair, but I tried."

"Would it have been easier in Europe?"

"Tweak, tweak, and my hair is done"

"Perhaps. Of course, today I do not know how children are brought up in various countries. Certainly in America they think too much of themselves. Fortunately I did not have that trouble, so discipline was easy for me."

![]()

The mending was completed. She stood up and went carefully to put her needle case in its place, then to the rather simple, uncluttered dressing-table.

Without apparent concentration she began to put on her eye make-up. There was a feeling in the air that I should go.

"I'm told you take care of all your own grooming, hair and everything."

"Oh, yes. I always have. Now with my lovely little electric hair iron from Belgium it is easier.

"I used to wash my hair every day, set it, dry it, and only then be ready for the theatre. It took three hours. Now I come in, plug in the hair iron, and tweak, tweak, I am ready. Very bad for the hair, of course."

I looked at the healthy, sleek mop of gold and found it hard to believe. "But surely you're lucky. You have a strong constitution?"

She rushed to a wooden backed chair and touched it for luck, giving me a look of "Don't tempt the fates."

"So far yes, thank God!"

"Are you religious?" I asked.

"Not really. I prefer people to ideas. In Birmingham just now they said to me, 'You must make time to see Coventry Cathedral.' I said I had not time, I was busy.

"At that moment I was sitting, as I did every night, with a young boy called Dennis, who worked the theatre lights.

"He has multiple sclerosis and is half paralysed, so each night I used to share my champagne with him and we talked and talked.

"'Come now,' they said, 'you have time,' I said I would rather be with Dennis and I stayed.

"Actually today I am rather excited. You see, when I left Birmingham I told him he had to write to me and he said he couldn't with his bad hands. Today I sent him a nice typewriter and now he can go bang with one finger and write me."

"So you do make friends on tour?"

"I'm not good at making friends. Only keeping the few I have. Now I must go and dress."

As we shook hands and I wished her luck in Australia she suddenly looked terribly alone. "Will you be there when I am? I know no one at all in Australia."

I said no, but offered to give her the names of some friends she might like.

"Yes, please, tell them to come backstage and say they are friends of yours. I should like that." She smiled and shook hands.

"No, I won't ring them, they will come if they want to."

Two things became clear quite suddenly. Marlene Dietrich is often very alone and always rather shy.

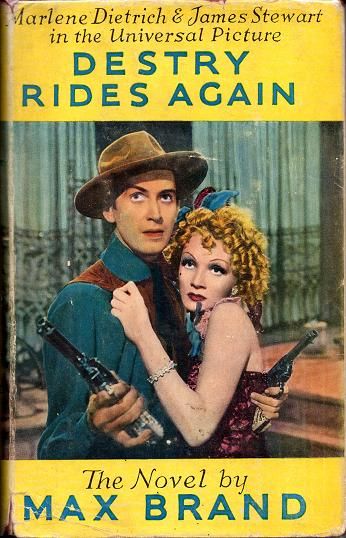

![]() |

| Dietrich, in front of impresario Binkie Beaumont’s London home. |

.jpg)

.jpg)

%2Band%2BFlight%2BLft%2BKenneth%2BJ%2BFisher%2Bboth%2Bof%2Bthe%2BRCAF%2Bposing%2Bat%2BEl%2BMorocco%2Bwith%2BMarlene%2BDietrich%2Bof%2Bthe%2BHMBL%2B(Hollywood%E2%80%99s%2BMost%2BBeautiful%2BLegs).png)

.jpg)

%2BLondon.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)